|

| Click on the picture to see the animated version |

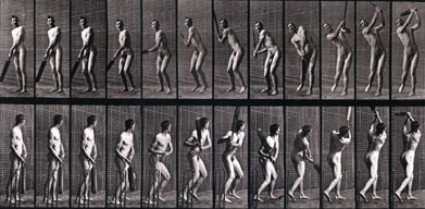

The animated example here is derived from Eadweard Muybridge

The dots represent the joints and the lines represent the bones. By reducing the figure to this simple form a framework can be built to represent movement. The Biomotion Lab Walker is an interesting example on the web of how to reduce a figure to its bare essentials, this example produces the illusion of movement with only dots representing the joints. The example goes farther and allows you to experiment with faster and slower movement and a male or female figure.

This is the basic structure for animation, for motion capture and for rendering computer animation for motion pictures and game animation.

The books documenting the photographs the Eadweard Muybridge took in the 19th century are a great place to start studying the figure in sequential motion. He used a black backdrop which had grid lines painted on it so that the observer of the photograph can locate the figure in space as it moves across the grid, then photographed clothed and nude figures of men and women and animals as they made common movements. These photographs were in effect some of the earliest motion pictures. He began his unusual career in the San Francisco area when challenge by Gov. Leland Stanford to answer the question of whether all four feet of a race horse actually left the ground during a gallop. He then continued his work with a study of Animal Locomotion

From Wikipedia and from Graham Wakefield's course site.

Drawing a picture or illustration of the human figure in motion starts from the same framework. Start with the abstraction of a skeleton or stick figure making the movement you wish to illustrate and add details to complete your drawing. These are two examples from E. C. Matthews' Cartooning and Commercial Art

Skeletons in action and action skeletons suggesting emotion.

Action skeletons and action skeletons clothed.

Harriett Weaver (Petey) calls similar action stick figures urch-purches.

This is from her book Cartooning Plus Good Drawing .

.

C. N. Landon illustrates action in his Course of Cartooning Action Plate 1. with these suggestions: "I have drawn a series of figure denoting the positions the figure assumes when a man takes one full stride in walking. There is a certain difference of ACTION in arms and legs. The shoulders twist a trifle when a man walks which throws the RIGHT ARM forward ad the LEFT LEG comes forward. When the RIGHT LEG moves forward the LEFT ARM follows. Study Figs. A, B, C, D, E and F carefully and note the position of arms and legs as the figure takes a full stride.

"Walk across the room and swing your arms naturally and you will notice that the arms and legs swing in the manner I have described.

"When a figure is drawn jumping the arms and legs assume a definite position. Fig. G denotes the position assumed when about to jump. Notice how the figure is balanced by raising the arms. Fig H. shows the same figure about to land. Note the natural position of the arms and legs. Fig. I shows a man throwing a weight. Notice here the same rules apply as in figures walking. The right arm is in a corresponding position with that of the left leg. Fig. J shows a man running. Here the same rule is brought out with greater force. The right arm is back and so is the left leg. The left arm is forward and so is the right leg. When drawing a comic figure walking you can lean the body forward more than in real life to get a comic effect. Drawing the arms and legs in the right position is one of the tricks every successful cartoonist uses in getting good action.

"In Fig. K we have a back view of a man walking. Fig. L is the same figure drawn in diagram form. Notice that the foot on which the body rests comes directly under the center of the weight. This is generally on a line directly beneath the head.

"Fig M is a little skeleton, with a few lines, based upon the correct proportions of the figure. Figs. O and P show how to indicate action. When drawing comic figure you can exaggerate these proportions. Take your pencil and pad and practice drawing a series of skeletons in various positions. Make them running, walking, pushing a wheelbarrow, writing, climbing a ladder, kicking, etc. This practice will enable you to fix in your mind the relative positions of the arms and legs and the direction in which to lean the body in expressing ACTION. Don't neglect this practice work, because it is really important."

Post about Duchamp's Nude Descending a Staircase, influenced by Muybridge's photographs.

Another post on the same subject by Time Out of Joint

Another post on the same subject by Time Out of Joint

Another animated gif, this one is based on Muybridge's Cricket Player.

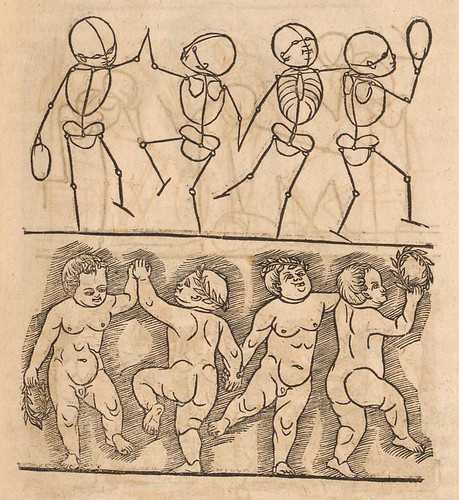

Study of figures in motion showing the movement of arms and legs first in the structure of the bones, then in the complete human form, from Trattato della Pittura by Leonardo da Vinci, a copy of which is currently exhibited in the National Gallery of Art. Notes on the exhibit: The Body Inside and Out., and a link to the Exhibit including a free catalog you can download at The National Gallery of Art.

Study of figures in motion showing the movement of arms and legs first in the structure of the bones, then in the complete human form, from Trattato della Pittura by Leonardo da Vinci, a copy of which is currently exhibited in the National Gallery of Art. Notes on the exhibit: The Body Inside and Out., and a link to the Exhibit including a free catalog you can download at The National Gallery of Art.eBook The Figure in Action

The Human Form in Action and Repose

investigates the motion of the human figure in photographs. The authors Phil Brodatz and Dori Watson published it in 1966.

investigates the motion of the human figure in photographs. The authors Phil Brodatz and Dori Watson published it in 1966.

In the 40s and 50s John Everard published books that included sequential images of figures.

Basics Animation: Stop-motion

The Advanced Art of Stop-Motion Animation

Stop Motion: Craft Skills for Model Animation, Second Edition (Focal Press Visual Effects and Animation)

No comments:

Post a Comment